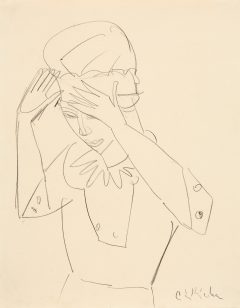

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Mädchen mit Hut (Gerda)

ca. 1912

Pencil on paper

34 × 27 cm | 13 1/2 × 10 2/3 in

Signed also stamped with the Basel estate stamp and numbered “B Dre/Ab 12” (revision in pencil “Ba”) and “K 2827” on the verso

The work has been registered by the Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Archiv, Wichtrach/Bern, Switzerland

The artist's estate; Private Collection G. F. Büchner, Berlin; Private Collection Germany

- Galerie Ludorff, "Muse & Modell", Dusseldorf 2014

- Kunstamt Neukölln, Saalbau-Galerie, "Ernst Ludwig Kirchner - Handzeichnungen. Sammlung G.F. Büchner", Berlin 1986

- Galerie Ludorff, "Muse & Modell", Dusseldorf 2014, p. 11

- Kunstamt Neukölln, Saalbau-Galerie, "Ernst Ludwig Kirchner – Handzeichnungen. Sammlung G.F. Büchner", Ausst.-Kat., Berlin 1986, no. 7 with ill.

After studying architecture, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner began painting and drawing as an autodidact. In 1905, together with Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Fritz Bleyl, he founded one of the most influential groups of artists of the 20th century: Die Brücke. His Dresden studio, a "Temple of Lust"1), is a meeting place for the German avant-garde. Here he produced paintings and above all drawings which, in a very short time, namely in fifteen minutes proclaimed by the artists, captured mostly naked women, children and couples in natural movements in skilfully set strokes.2) Our drawing "Kauernde Dodo", which shows Kirchner's Dresden partner, Doris "Dodo" Große, in an elegant pose on the famous leopard stool, is a typical example from this period.

In 1911 Kirchner left Dresden and Dodo to move to the capital Berlin. There, in the hustle and bustle of the big city, his style changed: the lines became sharp-edged and his brushstrokes feathery. Kirchner absorbed the motifs of the city and captured them on canvas and paper. Street scenes show ladies in fashionable clothing and with elaborate headdresses. Kirchner often portrays women from the milieu who dress up as widows with veils in order to remain unmolested by the police. His further choice of theme was decisively influenced by a meeting with two dancers: in a Tingeltangel bar he first met Gerda and later her sister Erna, who became his partner after a brief relationship between the artist and Gerda. Kirchner himself writes in retrospect: "The design of man was strongly influenced by my third wife (Erna), a Berlin woman who from now on shared my life, and her sister. The beautiful, architecturally constructed, austere bodies of these two girls replaced the soft Saxon bodies. "3) The artistic examination of their nudes educates Kirchner's "sense of beauty for the creation of the physically beautiful woman of our time. "4)

Our sheet shows a beautiful, young woman who, lost in thought and apparently unobserved, puts her hat up. Gerda's sensual, full lips and the hair that has been put up above her ear to form a snail indicate that she is Gerda. She wears a blouse with a sophisticated collar and button adornments on sleeves and neckline. Kirchner is able to skillfully capture Gerda's spontaneous, fleeting gesture in just a few strokes. One recognizes his mastery in the precise and rapid observation of the scene and its impressive implementation on paper. Looking back, the artist writes about his drawings under a pseudonym: "He [Kirchner] uses the entire surface of the sheet in question. Not only the lines and the forms formed by them, but also the unmarked part of the sheet form the picture. 5)

Note:

1) Felix Krämer, "Foreword", in: "Ernst Ludwig Kirchner - Retrospective", Exhibition Cat. Ostfildern 2010, p. 15.

2) "Naturally, [Kirchner] was particularly interested in naked people. Here he deliberately tore up the traditional way of studying the nude and created a circle of young girls in his studio, whom he studied freely in movement. [...] He saw the helpless dependence of contemporary art on antiquity, saw that there were other styles of at least as high a culture as Greek, but also saw that the path to a new modern one led only through a purely naïve study of nature without style glasses. Thus the Dresden years were filled by a fanatical free work after naked people in the barren studio (shop) and at the Moritzburg lakes. Davoser Tagebuch, 1925. Kirchner cites Kirchner as an anonymous critic of his art in a draft, possibly as a correction of Will Grohmann's text for his second publication on the artist (1926): Anita Beloubek-Hammer, "Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erstes Sehen, Das Werk im Berliner Kupferstichkabinett", Munich et al. 2004, p. 66.

3) Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, "The Work of E. L. Kirchner", in: Eberhard W. Kornfeld, "Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Nachzeichnung eines Lebens", exhibition cat. Kunstmuseum Basel, Bern 1979, pp. 332-345, here pp. 341, probably written in 1925/26.

4) ibid.

5) L. De Marsalle: "Drawings by E. L. Kirchner", in: Lothar Grisebach: "E. L. Kirchner's Davoser Diary, A Depiction of the Painter and a Collection of His Writings", Cologne 1968, p. 185.