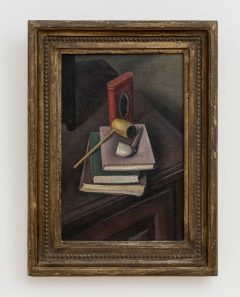

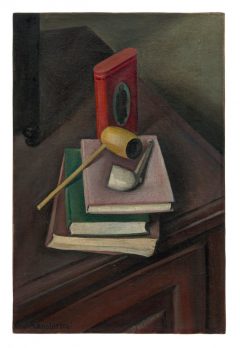

Alexander Kanoldt

Stillleben V

1921

Oil on canvas

38 × 25 cm / 14 15/16 × 9 13/16 in

Signed and dated also on the stretcher "A. K. 1101" and "Frowein" inscribed

Catalogue Raisonné by Koch 2018 no. WV 21.13; Work list 1921, no. 45

Provenance

Frowein Collection, Wuppertal-Barmen/South Africa/Canada; Private Collection Ontario, Canada

Exhibitions

- Galerie Ludorff, "Neuerwerbungen Frühjahr 2024", Düsseldorf 2023

Literature

- Galerie Ludorff, "Neuerwerbungen Frühjahr 2024", Düsseldorf 2024, S. 56

- Michael Koch, "Alexander Kanoldt 1881-1939. Werkverzeichnis der Gemälde", München 2018, Nr. WV 21.13

- Elke Fegert, "Alexander Kanoldt und das Stillleben der Neuen Sachlichkeit", Hamburg 2008, S. 166 + 292f., Abb. 41

- Kristina Heide, "Form und Ikonographie des Stillebens in der Malerei der Neuen Sachlichkeit", Weimar 1998, Abb. 310