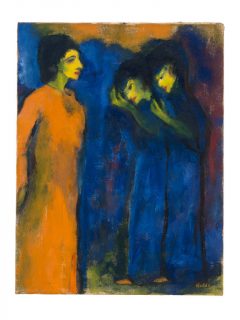

Emil Nolde

Huldigung

1947

Oil on canvas

88.7 × 67.5 cm / 34 15/16 × 26 9/16 in

Signed and also signed again and titled on the stretcher

In the artist's 1930 hand list noted as "1947 Huldigung" (Homage); Cf. the watercolor, "Huldigung (Homage)", from the series of unpainted pictures, in the collection of the Nolde Foundation Seebüll

Catalogue Raisonné by Urban 1990 no. 1296

Jolanthe Nolde, Heidelberg (the artist’s wife, directly from the artist 1956-2010); Private Collection West Germany (by inheritance 2010-2020); permanent loan at the Brücke Museum, Berlin (2014-2020)

- Galerie Ludorff, "Neuerwerbungen Herbst 2021", Düsseldorf 2021

- Emil Nolde. Der Maler, 15. Juli – 23. Oktober 2016, Brücke-Museum, Berlin (1. Station); 5. November 2016 – 5. Februar 2017 Kunstmuseum Ravensburg (2. Station)

- Nolde Stiftung Seebüll, "Emil Noldes späte Liebe. Das Vermächtnis an seine Frau Jolanthe", Seebüll 1. November 2013 - 30. März 2014

- Heidelberger Kunstverein, "Emil Nolde – Gemälde, Aquarelle, Graphik", Heidelberg 1958

- Kunsthalle, "Emil Nolde, Gedächtnisausstellung", Kiel 1956-57

- Städtische Kunsthalle, "Emil Nolde", Mannheim 1952

- Kunsthalle, "Emil Nolde", Kiel 1952

- Kunst- und Museumsverein, "Emil Nolde", Wuppertal 1951

- Galerie Ludorff, "Neuerwerbungen Herbst 2021", Düsseldorf 2021, S. 106

- Galerie Ludorff (Hg.), "Emil Nolde, Huldigung", mit Textbeiträgen v. Dr. Christian Ring u. Juliana Gocke, Düsseldorf 2021, S. 17, 20, 23, 24

- Magdalena M. Moeller, "Emil Nolde. Der Maler", München 2016, S. 188, Abb. 66

- Christian Ring, Nolde Stiftung Seebüll (Hg.), "Emil Noldes späte Liebe. Das Vermächtnis an seine Frau Jolanthe", Ausst.-Kat., Köln 2013, Nr. 21, Abb. S. 36

- Martin Urban, "Emil Nolde. Werkverzeichnis der Gemälde 1915-1951", Bd. II, London 1990, Nr. 1296

- Heidelberger Kunstverein, "Emil Nolde. Gemälde, Aquarelle, Graphik. Eine Privatsammlung", Ausst.-Kat., Heidelberg 1958, Nr. 12

- Kunsthalle, "Emil Nolde, Gedächtnisausstellung", Ausst.-Kat., Kiel 1956, Nr. 40

- Städtische Kunsthalle, Emil Nolde, Ausst.-Kat., Mannheim 1952, Nr. 36

- Kunsthalle, "Emil Nolde", Ausst.-Kat., Kiel 1952, Nr. 36

Emil Nolde: “Homage”, a Painting from 1947

Christian Ring

In Emil Nolde’s oil painting “Homage”, the entire left side of the image is occupied by a strikingly upright, slender, dark-haired woman with strong red lips and a complexion tinged with olive green. By holding her right arm slightly behind her back, she assumes a self-assured and proud stance. Her elegance is accentuated by a floor-length warm orange dress with a high neck and long sleeves. Her feet are not visible; Emil Nolde has cropped the bottom of this figure. On the right side of the painting are two women, bowing slightly, who approach the figure from a recessed area of the image. Their robes are equally long but bright blue, with elbow-length sleeves, partially revealing orange shoes. The pair raise their yellowish green forearms in a parallel gesture, one to chest level, the other to her intensely greenish yellow face, both with bold red lips. Only dark outlines distinguish them from the background, which is the same blue as their vestments. The background and venue of this encounter both remain indeterminable. The orange upper edge of the painting, which is the same hue as the dress worn by the single figure, also provides no indication. The floor is depicted in a shade of green, which may be a mixture of the orange, yellow, and blue of the pictorial zones above. The harmonious tone of the painting is due to the relationship between these three colours and their mixture. In this painting in particular, Emil Nolde proves himself to be a great magician of colour who had a decisive influence on the history of modern art. Black is only used as a hair colour and to delineate the figures from the colour background. Thus, with just a few brushstrokes, Emil Nolde gives each of the three protagonists their own character and grants them a strongly expressive power. The status of the women depicted is made unmistakably clear by their posture: the two women approaching the proud woman are there to revere her. With their bowed stance, they are paying homage to her, which probably led the artist to give the painting the title “Homage”.

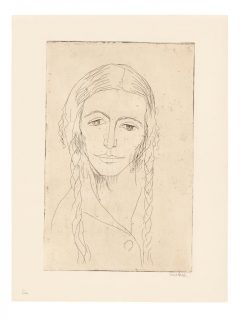

Emil Nolde, the Painter of People1

It is not clear who is being paid homage to and why. It is also unclear who the people in the painting are. Emil Nolde gives us no information about this. He is not a portrait painter in the proper sense of the term. His interest in the depiction of the character lying beneath the surface and the essential characteristics of those depicted led him to free figure painting. Emil Nolde emphasizes the significance of this complex of works in his entire oeuvre in his writings and letters in various contexts, including in his autobiography: “People are my pictures. Laugh, rejoice, weep, or be happy, you are my pictures, and the sound of your voices, the essence of your natures in all their diversity, you are the painter’s colours” (II, 144). Pure representation is not important to Emil Nolde; his creative freedom gains the upper hand and he produces new portraits and images of people in an open, intensely vivid formal language. The natural model is no longer the source of his knowledge, but rather his own inner self. Emil Nolde’s depictions of people reflect his view, how he, the artist, sees, experiences, and above all perceives the people depicted. Emil Nolde’s art always mirrors his perceptions, his introspection: “I was very interested in the human characters, in their free depictions in any fixed state, but also as living beings, and how they behaved” (I, 140). Emil Nolde’s interest is rooted in the representation of the character lying beneath the surface and the essential characteristics of the people portrayed. His images chronicle human encounters and family experiences, the tension between the sexes, but particularly feelings such as love, desire, fear, astonishment, curiosity or, as in this painting, humility. He leaves each viewer’s imagination to devise their own potential narrative.

Exhibition view

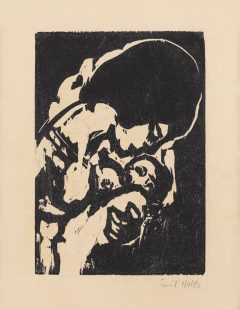

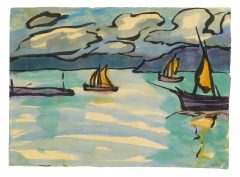

From “Unpainted Picture” to Picture

The oil painting “Homage” is one of a large series of works that Emil Nolde painted after the Second World War from his “Unpainted Pictures”. The corresponding watercolour from this series can be found in the collection of the Stiftung Seebüll Ada and Emil Nolde. Named by Nolde himself, the series is a group of over 1,300 small-format watercolours that were mostly painted from 1941 onwards, while he was forbidden from painting, although some definitely date back to the early 1930s. After the Second World War, Emil Nolde moved away from creating the small works on paper that were almost all he produced during his occupational ban from August 1941. In doing so, he perpetuated the establishment of a legend that styled him exclusively as a victim of the National Socialist regime. In 1941, the artist was expelled from the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts. He interpreted the first letter, dated 23 August, which forbade him from “any professional – even secondary – activity in the field of the fine arts” as a “Malverbot”, or a “painting ban”. A second letter, dated 20 November, demanded that “in the future you shall submit all your works to the aforementioned Committee [for the Assessment of Inferior Works of Art] before releasing them to the public”, and his friend, the Swiss jurist Hans Fehr, confirmed to him that the “Malverbot” of the earlier letter had thus been lifted. With his expulsion from the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts, Emil Nolde lost the right to ration coupons for scarce painting materials – oil paints and canvases. He increasingly turned to small works on paper, which he called his “Unpainted Pictures”. “I was prevented from acquiring material, and it was almost only my little, special ideas that I was able to paint and capture on very small sheets of paper, my ‘Unpainted Pictures’, which are to become large, real pictures, if they and I are able to do so” (IV, 126). In open contradiction to the myth of the secret creation of the “Unpainted Pictures”, there is proof that Emil Nolde began transferring watercolours from the series into large-format oil paintings from 1938 onwards. Emil Nolde wrote about the “Unpainted Pictures” in his memoirs: “If I were to paint them all, my lifetime would have to be more than doubled, but that is not possible on our naturally stringently ordered planet” (IV, 148). In the small-format works, he saw “the completion of the gift I have received, which I have obediently obeyed,” as he wrote in the manuscript for his “Unpainted Pictures”. “Many watercolours at that time [the South Pacific trip] and later, too, did not reach the height that I sought to achieve, I mercilessly destroyed them, or broke them up, trying, sometimes with the addition of ink and opaque colours, to paint my small, freely invented, mostly figurative designs. I did not feel bound to any natural model and I would paint, sometimes smiling a little cockily, sometimes creating dreamily. One brushstroke or line with my finger gave a figure a perceived movement or character, and I worked with all possibilities, here as in my art in general: my mediums are everything conscious, accidental, rational, or felt.” Emil Nolde tested the effect of the small pictures before converting them into oil by enlarging them first using an opaque projector. He described the discovery of this technique in his memoirs and placed it after 1945: “One day my wife and I went into an appliance shop to look at an opaque projector. We put a small sheet of paper in it and, one by one, five others that we had brought with us. It was quite astonishing to see these sheets projected onto the screen at perhaps a hundred times their original size. They looked so colourfully beautiful and almost finished down to the smallest detail that we were completely stunned. I suddenly saw six large finished pictures, but they soon disappeared again, just as quickly as dreams disappear” (IV, 147). Here, too, the artist seems to have slightly modified the story of his “Unpainted Pictures”. The musician Silvia Kind, who had met Emil Nolde in Berlin through his friend, the composer Heinrich Kaminski, gave a startlingly similar account of a stimulating evening in the 1930s, during which sheets of paper were placed on a projection apparatus: “And it was astonishing that none of the small pictures enlarged and projected onto a screen exhibited any weaknesses.”2 Emil Nolde was thus able to transfer motifs without altering the proportions or the general composition of the image. This knowledge offers an intimate glimpse into the artist’s working method and contradicts the topos, cultivated by the artist himself, that his art erupted out of him and onto the canvas. This was not the case with “Homage”. The ‘Unpainted Picture’ not only provided the idea and inspiration for the painting, but also served almost literally as a template for its execution in oil. Why, then, did Emil Nolde transfer the “fully valid” watercolours of his “Unpainted Pictures” into oil? With oil paintings he could reach a wider audience: this was due to the larger format on the one hand, and because of the technique on the other, which allowed the work to be permanently displayed in a museum or private living room, unlike the small-format and light-sensitive watercolours. As a technique, oil painting results in clearer colours than watercolour painting; they are also less mixed. Further minor deviations in detail can be noted, as well as a more solidified expression in the form overall, which transcends the limits of the other painting material. The oil paintings thus take on a certain solemnity in contrast to the spontaneous and light freedom of the watercolours.

Late Work

Painted in 1947, “Homage” is one of Emil Nolde’s late works. Building on his earlier œuvre, he develops his style into a powerful complex of works. The mature artist intensifies the harmonies and intimate relationships of his figure paintings by paring back his brush style and making it calmer. His real means of expression remains colour itself; he has perfected his impressive mastery of colour and light. The disintegration of form in colour is reduced; it is no longer the expressionist style that stirs and captivates the viewer, but the emotional content of his paintings. The artistic expression is softer and quieter, while simultaneously more emotional and profound – and thus ultimately more moving. The oil paintings become souvenirs, embodying a longing for the familiar. This is true of “Homage”. The painting was created in the year in which Emil Nolde celebrated his eightieth birthday. It was preceded by a year of deep mourning after his wife Ada died unexpectedly – despite a long period of ill health – on 2 November 1946, after forty-four years of marriage. The painting can therefore also be read as an “homage” to his beloved wife, who did not live to witness his birthday celebrations and great public recognition. In 1947, the oeuvre of the old master of German Expressionism was honoured with a series of exhibitions that also evaluated the evolution of his painting over the years. Ernst Gosebruch, for example, gave a speech in which he stated that Emil Nolde had “acquired the means for a completely visionary style in his old age, which in its soulfulness and spirituality represents the utmost that can be achieved in terms of artistic creative ability”.3

Jolanthe Nolde

The year 1947 brought an unexpected turning point for Emil Nolde when he met the twenty-five-year-old Jolanthe Erdmann once again, the daughter of his friend, the composer and pianist Eduard Erdmann, whom he had known since childhood. The pair were married on 22 February 1948 – a surprise even for their close circle of friends.4 Jolanthe Nolde restored a sense of happiness to the painter’s life and in the following years she gently encouraged him to continue his artistic work. She recalled how the artist resumed oil painting in his “workshop” – as he called his studio at Seebüll – after the winter. He viewed the small building, six metres long, seven metres wide, and connected to the main residence by the garage, as a “place of work”, “a serious place of duty” (IV, 90). It was presumably too cold to paint in the poorly heated studio during the winter. Jolanthe Nolde had to, as she recollected, “remove the dried paint plug that had formed over the course of the winter in many tubes of paint, arranged in rows according to colour. Of course, there was no lid on any of the tubes; they lay open once they had been used. He had a lot of different nails for the various colours that I would use to remove the dried paint. That was easy. Nolde does not paint with a palette. He squeezes the paint directly from the tube onto the brush.” In the spring of 1953, after a good five years of marriage, Emil Nolde made a testamentary disposition in favour of his young wife in order to provide security for her after his death. He did not make any alterations to the basis of the foundation that had been decreed in his will together with Ada in 1946. The name remained as it had been determined with Ada, the Stiftung Seebüll Ada und Emil Nolde, as did the stipulation that after his death the Seebüll house was to be opened to the public as a museum. Emil Nolde died on 13 April 1956, at the age of eighty-eight, and was buried alongside his wife Ada in the crypt at Seebüll. Six months after his death, Jolanthe Nolde left Seebüll so that the house could be opened as a museum. She was granted twenty paintings, twenty watercolours, and twenty prints by her husband in his will, as well as the farm, Seebüll Hof, his library, his cash, and some other household items. Jolanthe Nolde was allowed to choose the watercolours and prints from the estate herself. She had not completed any training or studies, nor did she have a profession, so the plan was for her to support herself by selling artworks. The paintings were selected by the artist himself, who noted the titles in shaky handwriting that betrays the travails of age. Christian Carstensen recalled that Emil Nolde told him which paintings that ‘his wife Jolanthe should have, determined that she should have a cross-section of his work’. Among this high-quality selection of oil paintings made by Emil Nolde himself is “Homage”, which Jolanthe Nolde did not part with until her death in 2010.

1 The quotations identified with Roman numerals and page references are taken from Emil Nolde’s four-volume autobiography (Cologne, 2002). The letters and manuscripts cited are in the archives of the Nolde Stiftung Seebüll. For further explanations see: Christian Ring, Emil Nolde – Die Kunst selbst ist meine Sprache (Munich, 2021).

2 Silvia Kind, Monologe, p. 142, cited from http://www.silviakind.ch/Monologe-Dateien/MONOLOGE.PDF, accessed 19 January 2021.

3 Ernst Gosebruch, “Emil Nolde”, speech at the opening of the exhibition on 19 October 1947, in: exh. cat. Emil Nolde, 242nd Exhibition by the Overbeck Society Lübeck, Behnhaus, 19/10/1947–16/11/1947 (Hamburg, 1947), p. 18.

4 Christian Ring (ed.), Emil Noldes späte Liebe. Das Vermächtnis an seine Frau Jolanthe (2nd edn., Cologne, 2014).

Browse our catalogue:

In the following video that we made in the course of TEFAF ONLINE 2021 Manuel Ludorff tells you some more exciting details about Nolde's painting.

Manuel Ludorff on the highlights of TEFAF online 2021