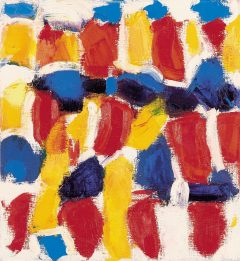

Max Ernst

De but en blanc

1959

Oil on wood

45 × 54 cm / 17 11/16 × 21 1/4 in

Signed and "59" dated

Catalogue Raisonné by Spies/Metken 1998 no. 3462

Price includes German VAT. Shipping costs are not included. All prices are subject to change and availability. Change region and currency

The artist’s studio; Edouard Loeb, Paris, France; Count Dr. Paolo and Countess Gretel Marinotti, Milan; Estate of Marinotti

- Galerie Ludorff, "40 Jahre 40 Meisterwerke", Dusseldorf 2015

- Palazzo Grassi, "Max Ernst. Oltre la pittura", Venedig 1966

- Galerie Ludorff, "50 Jahre", Part II, Düsseldorf 2025, S. 105

- Werner Spies/Sigrid Metken/Günter Metken, "Max Ernst Œuvre-Katalog Werke 1953-1964", Bd. VI, Houston/Köln 1998, no. 3462

- "Hommage à Max Ernst. Numéro spécial de la revue XXe siècle", Paris 1971, ill. p. 96

- Centro Internazionale delle Arti e del Costume (Hg.), "Max Ernst. Oltre la pittura", Ausst.-Kat., Venedig 1966, no. 17, p. 95

The painting "De but en blanc" by Max Ernst evokes different associations. The landscape-format picture support is almost completely coloured dark red, with only the upper edge - similar to a horizon - in a dark grey. Three shell flowers (fleurs coquillages), typical of Max Ernst's work, are depicted in the centre of the picture. Two larger ones in a spectrum of grey and white and a smaller one in a bright orange. The treatment with a palette knife creates a rosette-like structure that appears to be fanned out. The artist's focus is not on recognising the objects and interpreting the motifs, but rather on unrestricted and free interpretation. "De but en blanc" translates as "out of the blue" and is a very typical title, as it does not clearly refer to anything, but leaves the scope for interpretation open.

As a co-founder of the Cologne Dada movement and a pioneer of Surrealism, Max Ernst was always on the lookout for new ways of expression. Using various techniques such as frottage, grattage and decalcomania, the artist, who was born in Brühl in 1891, created random surface structures that served as a source of inspiration for landscapes, figures and forms. He expressly emphasises that his works should be interpreted freely and that no preconceived interpretation should impede the flow of thought. For him, it is important to track down hidden contradictions and work out ambivalent natural phenomena. The artist draws the poetry of his enigmatic works from the play of ideas and the indeterminacy and changeability of his figures. It is only on closer inspection of De but en blanc that the painterly result begins to unfold and take effect in us: We follow the sensualist appeal emanating from the painting. Our eyes remain in motion and move from form to form. As an active creator, Max Ernst has receded into the background; he remains merely the controlling authority who designs the shell flowers and carefully guides our visual experience.